"What does your tattoo mean?" | On Books as Life Savers

An exploration of Breakfast of Champions, free will and fate, and the idea that reading books can save lives.

I look down and can’t escape them.

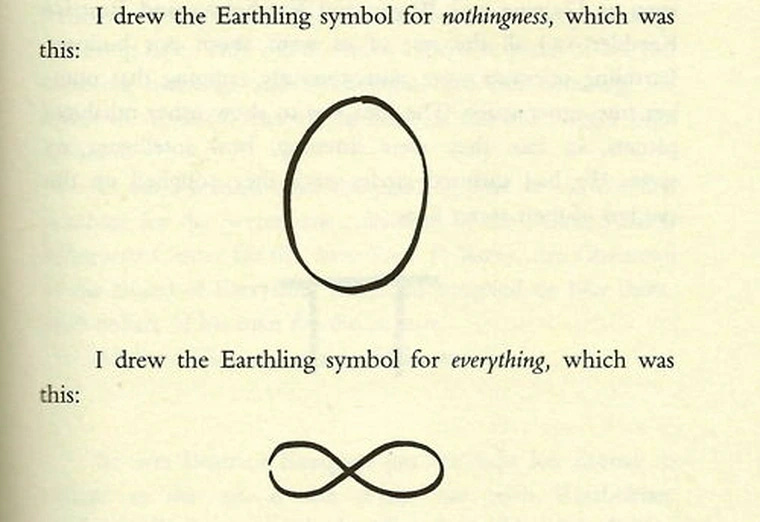

On my wrists, a set of fraternal tattoos are inked across the delicate skin. One, a simple zero, unbroken. The other, a twisted infinity, a toothless gap to the right side. They turn ten this July and if they were children, they would be starting fifth grade in the fall.

My students ask me all the time what they mean—a cow being abducted by an alien ship or an ornamental bird doesn’t warrant such an explanation, but they ask because children have an insatiable need to know. To explain this set of ink is a challenge, would be personal in a way that I set boundaries for frequently.

I began reading Vonnegut’s work in my junior year of high school. That year I sat behind Emily, a longtime friend I made in marching band, and during our downtime in our AP US Government class we would discuss the books we were reading. Both of us were writers and read avariciously. We became obsessed with the idea of banned books, and in the middle of work time we would trade our thoughts like contraband. Frequently we would get in trouble for this; but rather than stop us, it only made us hungrier. I started with Vonnegut’s most famous, scathing commentary on warfare, Slaughterhouse-Five – his black humor, his no-nonsense voice, and his writing style made me curious about his other works. So I picked up Sirens of Titan. Then another, and another until it snowballed into something I couldn’t quite name. Since then, I’ve read all of Vonnegut’s work—most of them in the five years following my junior year of high school, but others I revisited over the course of my twenties. I worked through Slaughterhouse-Five, Sirens of Titan, Player Piano, and Cat’s Cradle that year, but didn’t discover Breakfast of Champions until deep into my senior AP English Literature course. This was after Deadeye Dick but before Bluebeard, another of my favorites which I will save for another time.

I don’t remember much from my years in the public education system in Oklahoma, but the last two years a fog began to lift. It felt like I had been walking through a dense cloud, the kind you see obscuring mountaintops or valleys, barely able to see past the length of my arm. I was desperate for an explanation to pin to my apathy and disengagement with the world, and I felt relieved to find some sort of answer between the two covers of Breakfast of Champions. The novel is an amalgamation of Vonnegut’s chief complaints about humanity (but also about Americans), providing sharp-tongued commentary on our society while maintaining self-awareness of his privileged position as an educated white man that people tended to listen to. The first-person interjections throughout the narrative provide a window into the world of predetermined suffering, of egoism, and questioning of our own worldviews as correct (the answer: they aren’t). In a world of burgeoning American exceptionalism, the novel was a censuring of American egocentrism and the idea that our actions have no consequences on the people and communities surrounding us. I found it refreshing to read when the focus of much of the literature in my Oklahoma education focused on the classics of past centuries and foibles rather than on the modern historical influences of the last fifty to a hundred years. There is a balance to be struck (more on this later), and I found my literary education lacking in that regard.

The past informing the present, fate and free will, are all common thematic threads within Vonnegut’s work. The idea of suffering being predetermined is insidious, a sharp-fanged snake, and I wonder to what extent the present world has primed us for the indifference with which we regard one another. I often see a common joke circulating in circles of discussion on the internet, where similar feelings of “living in a simulation” or experiencing an occasional “glitch in the matrix” occur. One of my favorite songs from the past decade, “Rob a Bank” by Confetti opens with the lines:

“Would I be crazy if I thought the world was fake?

A game of simulation aliens play from outer space.

The players pick their religion,

That's what starts the competition,

Could be stupid 'cause I watch too many movies.”

We laugh at this idea and write it off; it’s just another meme, just another day moving through the same slog of endless tasks. But there’s a yearning there – a need for reassurance that we are more than our (sometimes) very boring lives. Vonnegut plays on this need to be the center of our own universe(s), and the pervasive egocentrism of our time is laid out bare. In the novel, it takes the form of others being machines existing in tandem with us and for us, stripping them of their own humanity. Vonnegut doesn’t allow us as readers to really understand the consequences until the very end of the novel, where the author loses his tenuous grip on the machines he thinks he controls. He’s aware of his own unreliability in his remembrance of his mother’s schizophrenia, or in the recollections of his own illness, but he still views the world through the lens of the Creator of [this] Universe.

The problem with this modern obsession with living in a simulation is that the agency of an individual is stripped away–it's a reduction of others to background noise when in reality they are the main characters in their own stories. In the Breakfast of Champions, the idea of individual people being and containing their own universes emerges during a conversation between Rabo Karabekian (a painter and the protagonist of Bluebeard, incidentally), Beatrice Keedsler (a Gothic novelist) and Bonnie MacMahon (a cocktail waitress). Their discussion of others having and telling their own stories is integral to Vonnegut’s discussion of literature as a reflection of reality, and subsequently, his central characters don’t exist in a vacuum but rather as a cog in a very large machine. Once you read Sirens of Titan or Bluebeard, you realize that the characters who are background noise of one novel are suddenly the keystones in another. Vonnegut’s observations about life and its intricacies struck me — and in my reflections of his work one page in the novel stuck out to me for this very reason:

As humans, I often think we grapple too much with trying to find the answer to the unanswerable question: What is the purpose of it all? In some ways, it’s a natural instinct of ours to question everything – after all, it’s the reason we got to space, the reason we’re still probing every angle of a problem until it’s solved. The novel explores the possibility, however, of the pointlessness of even asking the question – Dwayne was always going to end up in that cocktail lounge, was always going to go on a rampage. Vonnegut would always fall victim to the facade of control over his own creations, his own universe. Writing a place – a person – into existence is a messy business. It is akin to an act of God, but with the caveat of never being able to have real relationships with the objects of your creation. I often wonder if it's the same story for many writers. We spend hours, days, months, years entrenched in fictional worlds with fictional people. We can’t lose sight of our realities for the sake of fictional constructs, but those constructs are a key piece in dismantling the labyrinths which make us up.

Even now, a decade later, Vonnegut is still the only postmodern author I’ve read in their entirety, at least of the published works. I occasionally revisit them, but most often I reread Breakfast of Champions during times of personal unrest and restlessness. With each reading of the novel, I discover something new – but isn’t that the point (and beauty) of revisiting the impactful pieces of art and literature that touch us deeply? In a transitory time of my life, where I felt lost and disconnected, a piece of literature helped ground me. I am a decidedly different person now than I was when I first turned the page on Slaughterhouse-Five and Breakfast of Champions. I am more self-assured (barely) of my place in the world. More at peace that my purpose may change over time. More aware that I have finite time on this planet as who I am right now at this moment. I am a galaxy of my own creation – constantly being reborn of stardust, in the same way the author is in that cocktail lounge in the middle of that tiny Midwestern town. Who I am today will never be who I am tomorrow, and I find solace in the idea that I am a Creator in my own right.

Want to do more to support my work? Consider contributing to the tip jar.